Review of blending obligations across Europe

Blending mandates to meet renewable targets in the transport sector is one of the main drivers to promote biomethane production and uptake. But, with electricity and liquid biofuels outcompeting biomethane, the transport market is crowded. Demand-side incentives such as natural gas blending obligations now crop up in various European countries as the Member States transpose the provisions of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) into national legislation.

In this analyst update, Veyt takes stock of the existing/planned natural gas blending obligation rules in countries where the instrument is used to incentivise biomethane production.

France

The French Climate and Resilience Law foresees the creation of the biogas production certificate (BPC) system (read our analyst update). It obligates all natural gas suppliers to purchase BPCs for unsubsidised biogas, with the obligated amount based on total natural gas supplied. Currently, it is unclear how the GO and BPC systems would interact with each other (if at all). Article L.446-40 of the Energy Code specifies that the same MWh of biomethane cannot receive both a Guarantee of Origin (GO) and a BPC. The problem stems from the fact that GOs were created for the sole purpose of demonstrating the origin of renewable energy (Article 19, par. 1), while target accounting is not one of the functions (par. 3). The French legislators supposedly reasoned to employ BPC in lieu of GOs to achieve biomethane production goals, preferring demand-side incentives (quota/obligation schemes) over supply-side ones (subsidised biomethane production with the associated voluntary certificates). Thus, BPCs risk outcompeting French biogas GOs from a purely financial standpoint, drying up local demand for the latter.

Germany

The draft of the German blending gas obligation decree is yet to be seen, as the document is currently at a pred-draft stage. All details are yet to be uncovered; whether biogas GOs would be the default certification type remains to be seen, as there is still no official German gas GOs register and it is unlikely to be operational before 2025. Veyt observes that proposals like this one have been coming up occasionally, for the last decade, without success. Therefore, it will take some time before the law materialises (if at all).

Austria

The draft of the Renewable Gas Act aims to substitute 9.75% of the gas volume sold and at least 7.5 TWh (equivalent to a fifth of current EU biomethane production) with renewable gases from Austria in 2030. Suppliers can prove compliance by presenting the corresponding domestic guarantees of origin with a green seal, with the latter issued only if biogas meets the sustainability criteria. Thus, the system design suggests that biogas GOs and green seals would be intertwined.

The Act went through the Ministry Council on 21 February 2024, which is the final step before entering Parliament. There, two-thirds of the parliament members need to approve the act. The timeframe for the act to pass is limited, especially in light of the autumn 2024 elections; if it does not pass now, the next government could be left to deal with the file.

Portugal

The Portuguese ordinance will oblige gas suppliers to replace at least 1% of the volume of their natural gas with RFNBO or biomethane, which will also be the subject of a new auction (read Veyt’s analyst update). The government will create a new body, the Wholesale Supplier of Last Resort, that will purchase renewable gases on an e-auction before selling them to gas suppliers. GOs will either accompany the gases or be sold separately from them. So far, no date has been set for the auction.

Netherlands

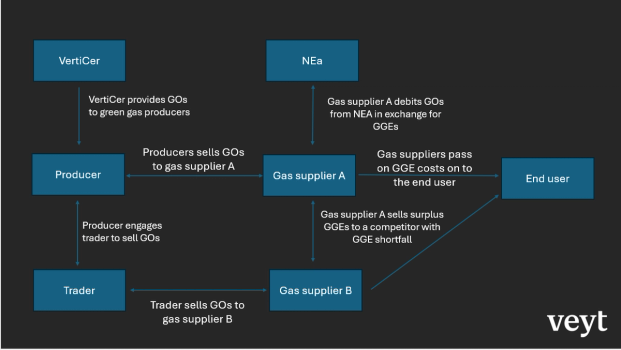

The Dutch blending obligation has been officially delayed by one year to 2026. Unsubsidised GOs will serve as a basis for receiving tradeable Green Gas Units (GGEs), however, they will be exchanged for GGEs by the Dutch Emission Authority (NEa) (see the functioning of the Dutch scheme in a graph below).

Green gas producers feed green gas into the gas network. VertiCer, the Dutch registry, acting on behalf of the Minister for Climate and Energy, checks whether production meets the requirements set under the Energy Act. If that is the case, GOs are issued to the green gas producers and registered in VertiCer. Energy suppliers can produce green gas themselves and receive GOs for this, alternatively, they can purchase GOs from producers or traders.

The energy supplier can then register the GOs and their associated characteristics with NEa, in the GGE register. Based on this, the GGEs are credited to the energy supplier's account. Since the blending obligation focuses on CO2 performance, the unit of a GGE is expressed in kg CO2 equivalent. GGEs will thus allow gas suppliers to comply with the blending obligation, without physical blending.

Note, only domestic production qualifies. Also, since only energy suppliers can register GOs in the GGE register, GOs will remain tradable within different markets but no more GOs will be registered than there is demand for GGEs from suppliers.

Market impact

Out of all the schemes, the Portuguese blending obligation scheme is the only one in force, while the Dutch bill provides the most comprehensive overview of the scheme’s functioning. The French BPC scheme could completely replace the biogas GOs, as the latter’s use is compromised and disincentivised under the current wording.

Countries that accept biomethane imports to fulfil blending obligations have the potential to stimulate biomethane production in other Member States, which could reduce the impetus to deploy supply-side incentives for stimulation. This in turn would have a bearish impact on the voluntary biogas GO market.